Inside Chevy's Big Bet on the Volt

<p>Every aspect of the new Chevy Volt, from its conception to its execution, exemplifies disruptive innovation. Here's how the old-school automaker overcame internal and external challenges to create a truly game-changing technology.</p>

This is the first part of a two-part series about the development of the Chevy Volt. This part focuses on developing the concept, and part two will focus on how the GM team delivered its pathbreaking car under incredible internal and external pressures.

When the Chevy Volt concept was introduced in early 2007, many doubted GM's ability to deliver. Even If it could be done, they believed it was impossible to deliver in late 2010. Yet somehow GM did deliver without compromise as evidenced by the widespread accolades including Motor Trend Car of Year 2010, Car & Driver 10 Best 2010, Popular Mechanics Top Products of 2010, and Green Car of the Year 2010.

I wanted to learn how GM did it and what other organizations can learn about bringing "disruptive" green innovations to market. "Disruptive innovation" is an unexpected advancement that usually combines technology and business model changes to fundamentally transform markets.

An example of a disruptive innovation is Ford's Model T. But an even broader disruption was implemented by GM's Alfred Sloan in the 1920's and 30's. Sloan is considered the architect of the modern corporation, with business model innovations that include establishing divisions, consumer credit, annual releases of new models, and creation of a supplier network.

I sat down with Jon Lauckner, who is currently president of GM Ventures. He was there when the Volt was just a twinkle in then Vice Chairman Bob Lutz's eye. Together with Bob Lutz, Lauckner is credited with defining the propulsion system for the Volt concept car that, at its unveiling in January 2007, created more buzz than any concept car in recent history. He then went on to lead the Volt program.

How to Shift From an Incremental to a Disruptive Strategy

The first step is for a company to consider the need for disruptive changes. This may sound obvious, but many companies tend to go the seemingly "safe route" with incremental improvements, line extensions and me-too copies of market leaders. And even current market leaders need to think ahead to the next "big thing."

During a period of stability and order, such as the time after the Second World War for GM, the future was fairly predictable and an incremental approach, building on existing trends was a practical approach. As Lauckner stated, "History provided a pretty reasonable prediction when developing a forecast of what the future would probably look like."

GM found the days of using history as a predictor was risky given rising complexity where new competitors were emerging, technology was accelerating, new markets were opening, regulations were intensifying, natural commodities were under stress and customer trends were changing. Lauckner declared "In an environment of rapid change, rather than rolling the ball forward with incremental improvements, a better position is to do something bold to drive future success."

Volt Inception

Early in 2006, then Vice Chairman Bob Lutz had an idea after seeing what Tesla was up to with its lithium battery electric vehicle. He invited Lauckner, who at the time was Vice President of Global Program Management, to his office to discuss his vision of a new EV concept car. The purpose of the EV was to achieve petroleum independence -- this was a goal that everyone could embrace, from energy hawks like Lutz to dyed-in-the-wool treehuggers to those of us in-between.

Lauckner said, "We sat in his office where Bob outlined his vision of a pure EV with a range of hundreds of miles that would do everything a regular passenger vehicle does today."

Developing another electric vehicle for GM was a bold move. After the failure of GM's EV1 in the nineties and the success of competitors' hybrids, any new entry had to be fundamentally different from both to achieve the goal of oil independence:

• Unlike the hybrids, GM's new EV primary power source needed to be electricity, and• Unlike 2-seat EV1 that was positioned as a commuter car, GM's new EV needed to appeal to mainstream passenger car buyers

How to Transform the Vision into a Customer Focused Design

The design started and ended with the customer. Although GM, its suppliers and other stakeholders would need to deal with massive technology complexity while developing a very different propulsion system, the customer would find any new technology simple.

Above all, the design intent that became sacrosanct to the Volt program was to ensure that the customer could relate to the Volt. The customer could not be intimidated by the car or view it as some exotic toy or find it out-of-step with how the customer used a car. It would be effortless. For example, the Volt would need to carry at least four (unlike the EV1), be fun to drive, and electrical charging would require no special skills or equipment and a reasonable amount of time.

This second generation EV, unlike the EV1 would also need to be affordable. EV1 did not have a purchase option and was leased at more than $600 per month in 1996. Financial incentives in some areas reduced the price to under $500.

The Volt, in contrast, will lease for $350 a month and when the reduced operating costs are considered, the Volt is a price competitive with traditional ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) vehicles. Lauckner estimated that "Volt operating costs are about $100 less per month compared to a traditional petroleum-powered vehicle."

One other consideration was the macro environment. At that point in time (early 2006 when starting the design), no one predicted that the U.S. Department of Energy would be sponsoring EV projects and public infrastructure for charging. Despite some infrastructure in-place, there is still limited public charging in most of the US.

Lauckner described, "Rather than Lutz's original vision, which would require an enormous (and very costly) battery that would somehow have wheels attached, the customer would be much better served with a vehicle that had a smaller battery."

Almost 80 percent of the population in North America drives 40 miles or less each day. The average mileage in Europe is consistent with the U.S., at 65 km or 40 miles. So, a vehicle designed around a very large battery that would go unused most of the time made no sense to Lauckner.

A battery, using today's technology, is also a bulky, expensive and heavy component and minimizing it would provide space, cost and mass benefits. The goal was to find the optimal size battery where most people most of the time would drive using electricity from the grid, the new car's primary fuel.

One other issue with a large battery is charge time. A battery that could provide 150-200 mile range (approximately 30kwh of energy) would require 32 hours to charge using a normal 120V household outlet. That would make it impossible to recharge the battery overnight. Even with 240-volt outlet, charge time would still require about 16 hours for recharging.

Yet drivers on some occasions drive more than 40 miles or have an unexpected trip before the battery can be recharged. To handle this "use case," a small gasoline engine, or "range-extender," was added to create electricity while the vehicle was driven. The Volt could then operate normally until the battery could be recharged from the grid.

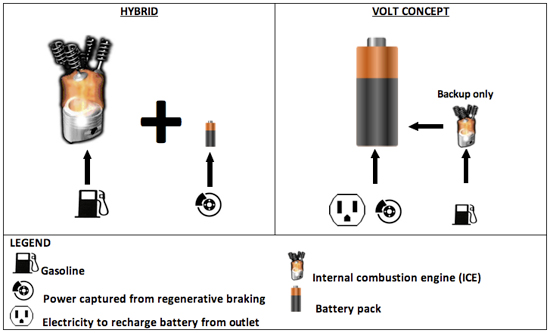

This elegant solution was disruptive when compared to the hybrids that used a small battery to supplement a large internal combustion engine (ICE). Instead, the Volt concept was to use a small internal combustion engine to generate electricity to supplement a large battery and drive an electric motor. Note diagram below.

How to Compare Design Options

Working with a small team of experts, Lauckner further refined the design of the concept car that he had described and sketched for Bob Lutz. "I pulled out the pad that I had used to sketch out the main design features of the new car with Bob and we further detailed the key attributes of the car and got working on the final design." He leveraged the sum total of his knowledge and experience to develop the Volt design.

Lauckner is a 30-year veteran of GM with a variety of leadership roles including international assignments in South America and Europe. He is a third generation GM employee trained as an engineer whose technical education was rounded out with a Sloan Fellowship at Stanford's Graduate School of Business.

What Lauckner did intuitively, the rest of us can do by completing a "trades analysis" where the trade-offs of the various options are evaluated. The current approach should be included in the "trades analysis" as a baseline to understand what improvements and limitations that new approaches provide.

The most beneficial aspect of a "trades analysis" is the conversations it elicits when rating the baseline and various options. Although trades analysis often start with pros / cons lists, it is a more disciplined approach since it ensures that the various options all consider the same evaluation criteria. It forces the team to remain focused on the evaluation criteria and not force the criteria to fit the solution. It is also useful to capture data that is uncovered iteratively when knowledge is more diffused across and outside the organization.

An abridged example of a "trades analysis" prepared by the author for illustrative purposes is outlined below.

Lauckner concluded that "After reviewing the options, we realized, WOW! Although it is unconventional, the Volt approach is an idea that could be a 'game-changer.'"

In part 2, read how the Volt went from being an interesting idea to the most important program at GM after the wildly successful introduction of the concept car. Lauckner and the team now had to deliver a new car in an unprecedented three years while introducing incredibly complex technology. In the middle of the program, the Great Recession started pushing GM into bankruptcy.