Building a smart city, one streetlight at a time

<p>Schneider Electric and the City of Boston find that the key to more intelligent, efficient cities starts with simple projects.</p>

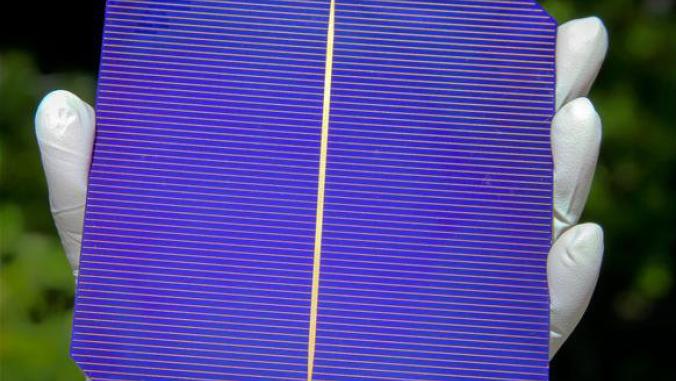

LED streetlight, San Luis Obispo, Calif., by emdot via Flickr

Learn more about smart cities at the GreenBiz VERGE Salon in New York City tomorrow, and at VERGE SF, Oct. 27 to 30.

The vision of a smart city decked out with millions of sensors feeding useful information to city officials and citizens is almost out of science fiction. To reach that point, though, it’s best to focus on something much more prosaic, such as helping citizens find parking spaces or switching out the bulbs in streetlights.

Cities around the world have long-range initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and better prepare cities for severe storms and other climate disruptions. But in most cases, achieving those goals with top-down, technology-driven projects is bound to stumble, said Charbel Aoun, president of smart cities for Schneider Electric.

“As much as we believe technology is critical to enabling smart cities, we avoid talking about technology,” said Aoun. “Smart cities is about cutting-edge innovation, but cities don’t like innovation — they can’t afford to fail.”

Instead, city officials need to modernize their infrastructure one chunk at a time and create a technical architecture that allows them to integrate their IT systems with their operational systems — electric and water grids, transportation systems and other infrastructure.

Schneider holds meetings with city officials to discern their priorities and then seeks out a project that can demonstrate some sort of energy savings, such as building efficiency upgrades. Ideally, those savings can fund further work. “You have to sell the value to the mayor, the management and the different department heads,” Aoun said. “It’s the basement connecting to the data center connecting to the mayor’s office.”

Light-bulb moment

The challenge for many cities is that once a city decides to install Internet-connected equipment, it quickly exposes organizational problems.

Consider streetlights. City departments are expert at operating streetlights and know who suppliers are and when upgrades are needed. But what happens when an LED street light is also a platform for providing wireless Internet access, security cameras and air quality monitors?

The streetlight goes from being a piece of equipment managed by the energy or traffic department to a high-tech device that needs to be integrated into back-office IT systems and monitored for network security. Rather than have the traffic department manage this equipment, it’s best for IT departments to have responsibility, said Aoun.

Buy-in from the budget keepers

Financing new initiatives is a challenge for cities, many of which face big budget deficits. The City of Boston managed to finance a number of energy-efficiency initiatives by getting two types of budget people to talk to each — those in charge of capital expenditures and those in charge of operating budgets.

By demonstrating that a building efficiency project could reduce operating budgets, for instance, the city was able to free the funds from the capital budget for a number of efficiency upgrades, said Todd Isherwood, an energy project manager for the City of Boston, who spoke at an event organized by Schneider Electric. An upgrade to LED street lights was able to save a substantial amount of money when utility rebates were figured in.

“The savings opens up a discussion,” Isherwood said. “None of my colleagues will move on the budgets unless there is money that can be saved.”

Those efficiency projects have led to a broader initiative to benchmark all of the city’s buildings and report their energy performance data. Once all the information is collected and consolidated, facilities managers can start to prioritize efficiency upgrades or make simple behavioral changes, such as deciding on how best to turn heating and cooling off at schools.

Over time, the city will get data on which buildings have combined heat and power units and can operate independently in the case of power outage, Isherwood said. Those buildings could act as shelters in the case of a prolonged outage.

A few cities in Europe have plans to create a “city operating system” that will allow developers to create applications with sensor data. But most cities don’t have the resources or the technical staff sophisticated to take on these types of grand projects, said Laurent Vernerey, CEO of Schneider Electric in North America.

“If (a smart city project) is not something thing that will be visible to the citizen, it’s going to be difficult,” Vernerey said. “As a mayor or city manager, how can I make their life easier? When they find an angle like this, then it opens doors very quickly.”

Top image of LED streetlight in San Luis Obispo, Calif., by emdot via Flickr