How I learned to stop worrying and love the exponential

Unfettered growth long has been seen as an enemy of resource efficiency. One school of thought — exponentialism — contends that plenitude, not scarcity, will result from our most daunting challenges.

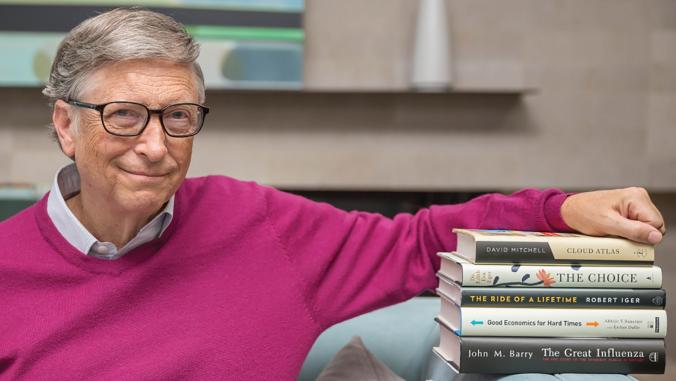

Long ago, in 1978, I met Dr. Strangelove — or part of him. And what he told me still rattles around my brain, shaping the way I think about the growing enthusiasm for the sort of “exponentialism” advanced by people such as Wired magazine Senior Maverick Kevin Kelly and X Prize founder Peter Diamandis — a worldview I developed early antibodies against.

Let me explain.

As teenagers in 1964, we laughed at Stanley Kubrick’s film “Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” With the Cuban missile crisis painfully fresh in our minds, this dark satire helped boomers enjoy a lighter side of what some saw as an inexorable slide toward nuclear Armageddon.

The film’s central protagonist was an ex-Nazi, now science adviser to American President Merkin Muffley. Both Muffley and Dr. Strangelove were played by Peter Sellers. And the Strangelove character, it later turned out, was partly modeled on Herman Kahn. He was famous, or infamous, as an architect of America’s MAD policy of mutually assured destruction — and a powerful influence on the country’s nuclear weapons strategy.

When the European end of Kahn’s Hudson Institute invited me to write a short report on the environmental challenges of the early 21st century, I zeroed in on four already looming in the late 1970s, two of which were climate change and ocean health.

All well and good, but Kahn — whose politics were to the right of Genghis — was unimpressed.

As he told me (and I'm paraphrasing): “The problem with you environmentalists is that you are like motorcyclists headed toward a chasm. Your instinct is to stamp on the brakes and try to steer away — when maybe you should be opening up the throttle and zooming across.”

I confess I thought him slightly mad. And when I later heard of the Strangelove link, it made sense. But over time I began to see what he was driving at. Perhaps he had the daredevil stunt rider Evel Knievel in mind, but his key point was that if you believe that something is impossible, it will be.

But people like him — he died a few years after we spoke — embrace the motto of the U.S. “Seabees” in the Pacific campaign during WWII: “The difficult we do at once; the impossible takes a little longer.”

Breaking through

I quoted this line during our 2012 Breakthrough Capitalism Forum, but it has been back in my mind as we have evolved our Breakthrough Forecast.

This explores market sweet spots likely to evolve in the Breakthrough Decade, from 2016 to 2025. These are some of tomorrow’s exponential growth markets in embryo.

But as we worked to aggregate market projections and valuations, I experienced an increasing sense of unease.

Yes, I have long believed in the capacity of capitalism to evolve solutions to major challenges more effectively than the alternatives. In 1986, I even coined the term “green growth” — and when we founded SustainAbility in 1987, its strap-line for years was “The Green Growth Company.”

Equally, the economists who lived on in my memory after I gave up a university course on economics in 1968 were Nikolai Kondratiev and Joseph Schumpeter. Both were detested by many mainstream economists, but they had argued that periods of rapid economic growth are followed by periods of economic decay, or “creative destruction” (PDF), before the cycle turns again.

That made abundant sense to me at the time, and still does. Contrariwise, as an environmentalist I also had developed those antibodies to exponential growth. The Limits to Growth (PDF) team and people such as Lester Brown had hammered away at pure-play exponentialists.

But the Schumpeterian in me knew that there would be times when the old order (say coal in today’s world) would give way to the new (say renewables in tomorrow’s world), and sometimes in remarkably short order.

Instead of facing what economists call the law of decreasing returns, some entrepreneurs would head into an era of increasing returns.

Plenitude or scarcity?

On April 13, 2005, I made a pilgrimage to Pacifica, south of San Francisco, to see Wired magazine’s chief maverick, Kevin Kelly.

When I read his books “Out of Control” and “New Rules for the New Economy,” his idea of increasing returns powerfully hooked my imagination.

Noting that he wished he had used the term “Networked Economy” rather than "New Economy,” Kelly explained that a network is a “possibility factory” — and that increasing returns ultimately would project us into a world of “plenitude, not scarcity.”

That plenitude torch also was picked up that same year by Peter Diamandis, who had founded The X Prize Foundation.

This remains one of my favorite organizations in the world of breakthrough innovation, alongside the Global Opportunity Network. More recently, Diamandis laid out his unapologetically cornucopian forecast in “Abundance,” a book subtitled, “The Future Is Better Than You Think.”

In the same spirit, Diamandis later co-founded the Singularity University with other exponentialists, among them Google’s Larry Page and Ray Kurzweil. The mission: “To solve humanity’s grand challenges.”

That bold ambition is underscored in SU’s latest impact report (PDF). The first paragraph begins: “Prosperity and growth are no longer measured only by wealth and revenue generated, but also by the rate at which new solutions to humanity’s challenges are created and become widely available.”

There’s something here that stirs the soul — or mine, at least.

It may be that I am learning how to stop worrying about the excesses of exponentialism — and to love the sheer scale of these people’s ambitions. There’s a symmetry, too.

Exponential dynamics that can take us down also can take us up. And knowing that there will be exponential upsides through the next decade is a refreshing change from the exponential downsides I covered in that long-ago report for Dr. Strangelove.