The robots eyeing my job

Beware the mechanization of everything, even desk-based knowledge workers. Even the bees are swarming.

The last thing I expected when attending the launch of the London Science Museum’s new Robots exhibition was to have a leading robot maker warn me that my job was at risk of roboticization. But when I handed my business card to Rob Knight, of Maxon Motor’s Robot Studio, his eyes lit on the job title: Chairman & Chief Pollinator. The way things are going with honeybees, he commiserated, it’s only a matter of time before nano-drones zoom in — and even human-to-human cross-pollinators such as me could be in line for disintermediation.

I assumed he was joking, at least with the last bit, but the robot revolution is proceeding at such a blistering pace that scarcely a day passes without another robo-breakthrough announced — or another robo-Frankenstein story exposed.

The day before the exhibition was opened — in part by a robot, RoboThespian — the Financial Times carried a full-page investigative article on the death-by-robot of a 20-year-old worker at an Ajin USA auto parts in Alabama. When an industrial robot stopped moving, she and three colleagues crawled inside the safety cage to try to get it going again. At which point it sprang back into life, crushing her. She died the next day, once taken off a life-support machine.

The very presence of that life-support machine underscores the way in which our working and living environments have been colonized by machines. Thanks to miniaturization and design they are less obtrusive than they once would have been, but the ways in which next-generation robots might elbow aside not just coffee shop baristas but even surgeons is suggested by Kodomoroid. Made in Japan, she was billed as the world’s first robot newsreader.

For anyone employing ordinary mortals to do repetitive tasks, the temptation to substitute robots must be intense at times. During a recent strike by Tube (subway) drivers in London, stranded passengers must have wondered how long it will be before all trains are fully autonomous — as they already are on at least one line.

And British insurance giant Aviva recently asked its 16,000 employees whether their jobs could be done better by a robot? Employees who answer "yes" will be retrained, we are told.

The world’s trade unions are wondering how to respond. The U.K.’s biggest union is Unite, with some 1.4 million members. They are increasingly minded to embrace robots, rather than fight them. To protect the jobs of their 95,000 members in the U.K. auto industry they are developing a strategy designed to help members prepare for a world of driverless cars, electric drive systems and increasingly robotic production lines.

Hopefully, the result won’t be like the legal reaction to early versions of the horseless carriage, where new laws required a car to be preceded by a man walking along with a red flag.

Whatever the general public thought about embryonic automobiles, today’s surveys suggest seismic fault-lines in public attitudes to the march of the robots. A recent survey by the Financial Times and Qualcomm shows the global elites — with higher educational and income levels, particularly those living in capital cities — to be much more enthusiastic than the general population.

We should expect pushback not just from workers but also from those whose financial interests are threatened. Consider investors in and owners of office property, including pension funds. I read recently of an office block in a northern city that had been leased to a firm of lawyers for 15 years. Offering a steady annual return of 6 percent a year, this should have been an attractive investment — but the owners were surprised when one likely bidder turned down the deal.

The reason: New forms of artificial intelligence already can read hundreds of pages of complex legal information every minute, sorting documents and identifying potential risks. As lawyers and other service professionals are replaced, the demand for offices could start to shrink, at least in vulnerable, outlying regions.

A study by McKinsey last year concluded that while fewer than 5 percent of occupations include activities that could be entirely replaced by automation, some 60 percent have significant elements that could be "roboticized." The firm estimated the wage bill that eventually could be automated in the five biggest European economies at $1.7 trillion, the equivalent of 54 million jobs.

The implications for such economies — and for the wider sustainability agenda — remain unclear. But how fascinating to see the U.K.’s Serious Fraud Squad using an artificial intelligence system to expose large-scale bribery and corruption at Rolls-Royce. Software to digest data has long roots, but the latest algorithms also can extract information from text, tables and pictures.

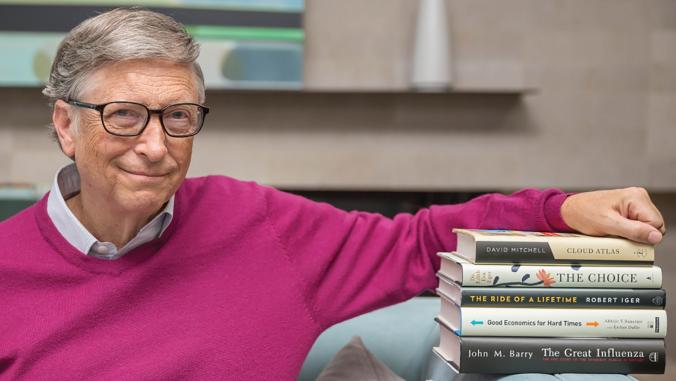

Bill Gates started something of a firestorm when he argued that robots should be taxed, both to slow down their deployment and to give us all time to adapt. His critics argue that lagging productivity in many countries, including the United States, can be addressed only by spurring the next wave of mechanization. Such controversies likely will rage decades.

When it comes to my own role, I’m not losing any sleep, yet. But the world’s honeybees — under threat on so many fronts — should be looking over their furry shoulders. Eijiro Miyako of Japan’s National Institute of Industrial Science and Technology has modified a commercially available quadcopter to create a "pollinator-bot" to transfer pollen from anthers to stigmata in flowers such as lilies and tulips. It seems to work.

From battlefields to wrecked nuclear reactors to pandemic "hot zones," robots go where people fear to tread. But the day will come when they begin to come in from the periphery into the core, and in growing numbers. That’s why we’re engaging experts in digitalization, mechanization and robotics in our Project Breakthrough program — while there’s still time.